I’ve been chronicling an experiment I ran over the summer with my gaming group to play a different RPG every week, and try to keep a contiguous storyline going. While the experiment itself is over, I’m a little behind on the articles. If you want to read from the beginning, the first article is here.

I’ve been chronicling an experiment I ran over the summer with my gaming group to play a different RPG every week, and try to keep a contiguous storyline going. While the experiment itself is over, I’m a little behind on the articles. If you want to read from the beginning, the first article is here.

And so we come to the end. I decided to end the summer with a session of Dread, which I had never played before, and neither had my players. If you know anything about the system, you know that we wanted to go out with a bang (or at least we were all ok with the high likelihood of dying…)

This session saw the players’ Shadowrun characters returning to their home base after a successful heist, and passing a spaceport on their way. As they were driving by, a salvage craft was lifting off, lighting up the early morning sky. Their Dread characters were the ones on the craft…

Dread

For this session, I selected the “Beneath a Metal Sky” scenario that is included in the Dread rulebook. According to the author, it is the “middle” scenario in terms of difficulty to run, but in reading through the other two, it was the one I felt most comfortable with. Bonus points for it being a space scenario, which fit nicely with our sci-fi heavy summer.

There will be no spoilers here, except to say that the scenario takes place on a spaceship. That, I believe, is the reason I was most comfortable with the scenario – like a dungeon, it is a confined space. The characters could not move beyond those bounds, so it made the environment something manageable for me. As a result, I was able to focus more of my attention on the story (and the rules) as it took place within that confined space. And there is the reason *most* beginning DMs are comfortable with the dungeon as an adventuring locale. But I suppose that’s another post for another time.

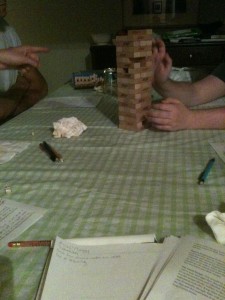

Dread is a unique RPG in many respects, but to the casual observer, its most defining feature is the use of a Jenga tower for action resolution. If your character wants to do something difficult or otherwise story-impacting, the player must draw one or more blocks out of the tower. If it topples, the character dies or is otherwise removed from the game.

As gameplay begins, two other aspects of the game immediately stand out – the lack of a character sheet (as it is traditionally understood) and, to a lesser extent, the Theatre of the Mind (ToTM) gameplay. Since there are many other RPGs that embrace ToTM, I will not rehash the pros and cons here, and instead focus on the unique “character sheet” that is used in Dread.

In Dread, the character sheet is called the Character Questionnaire. It does not contain a single number, skill name, or stat. It is, as the name suggests, merely a list of questions about the character that the player must answer. Most questions do two things – they tell the player a little something about the character while asking a question about motivations, personality, or past events. As an example: “Who was there when you killed your sister?” defines a piece of the character’s past while still leaving motivations, events surrounding the act, and a myriad of other details up to the player.

Needless to say, the beginning of the session was consumed with players filling out their questionnaires. But at the end of 45 minutes, I think my players had a better idea of who their characters were than most players of other RPGs have after years of playing.

Once the questions are answered, that’s the character. Period. If something in a player’s answers suggests that the character might be good at something, then the character is good at it. The elegance of this approach (especially for a story heavy game) cannot be overstated. Every RPG aims to define the character under the player’s control. Most use numbers as the primary indicators. Numbers are concrete. You can compare them to other numbers. I can understand their popularity. But while numbers are good at defining what a character does or can do, they’re really crappy at defining who a character is. Ironically, although most systems focus more on the former, the latter is what really drives a good story. And RPGs are all about the story.

In the end, only 2 of the 5 characters survived, but everyone had a blast. This is one that I’m sure we’ll be coming back to. I just wish there was more support out there for it. Where do you find Dread playsets? (I had the same problem with Leverage…)

What I Learned

I think the biggest lesson I learned from running Dread was the power of questions to help players define their character’s background. The questions in the Character Questionnaires were not vague – they were oddly specific in fact – but still left plenty of room for the players to play the sort of character they wanted. For example, the question “Who else was there when you killed your sister?” is at once oddly specific and completely open ended. Yes, the question is telling you that the character killed his sister, but why? Was it an accident? Premeditated? What were the events surrounding the act? And was anyone witness to it? Is the character aware of the witness? I should note that the Dread questionnaire asks for more than names when answering such a question. It asks for the motivations and events that would drive a person or persons to end up at the death of your sister. There are many directions that the answer could take, and in the process of musing upon and writing down the answer to such questions the player begins to really flesh out a personality for the character under her control.

One bit of advice from the book that I also passed along to my players bears repeating here:

When filling out a character questionnaire, you should always assume the presence of a silent “and why?” at the end of each question. It will create a better understanding of the character. The answer will cover more ground, and there will be less room for misunderstanding during the game itself. The more times you ask yourself “and why?” about any of the questions, the further and further you fall into the depths of the character, To take a seemingly innocuous question and apply an exaggerated example: “What’ll you have to drink?” Whiskey, on the rocks. “Why?” Because I’m a weary man with little use for frivolous and fruity drinks. “Why?” Because I have seen things that have made me question my own sanity. “Why?” It is the nature of my occupation to scour the world for things we were not meant to know. And so forth.

This, more than anything else in Dread, is applicable to character creation in RPGs at large. Delving deeper into the why’s of a character’s past (or even current) actions will always help players create a richer, three dimensional character.

That’s right – while the Questionnaire is the entirety of the character sheet in Dread, there is no reason why you cannot create one for the characters in your RPG of choice, as a supplement to the character sheet. At first, players may balk at you vaguely defining pieces of their past, but in the end I think all involved will find it to be an enriching experience. (Especially those players for whom the entirety of their character’s background is “My character is an orphan.” I mean really, whose character isn’t?)

You can buy Dread here. (ps – The book comes with 100 or so generic questionnaire questions. If you want to create background questionnaires for your players, it’s worth the price of admission alone.)

Also, you can follow Dread designer Epidiah Ravachol on Twitter.

Next time: The Big Wrapup ™

I first heard of this system about twenty minutes ago when this series of articles was linked to on my facebook wall. Now I reeeeeally want to play Dread! The questionnaire style sheet intrigues me. I’m sure some of those questions would also be a good place to start if you need to make a character in any system but don’t have a concept or back story yet. Thanks for posting!!

Glad you enjoyed it! Yes, the Dread questionnaire is a great way to finish (or start!) a character creation session for *any* RPG. If you want to do something like that, I highly recommend picking up the book just for the 100 or so sample questions that occupy the bottom margins of the book.

I think I’ll be doing that. Thanks for the series, Benoit!

No problem. I enjoyed running the experiment, so it’s a win all around!