(Digital?) Storytelling: Lessons from Interactive Fiction and Tabletop Gaming

Only a year or two after I started GM’ing seriously, I got involved in Interactive Fiction (often abbreviated as “IF”) writing with a cyberpunk adventure game called Orchestra. My crummy setting naming skills and limitations of the platform I was building it on notwithstanding, it received generally positive feedback from the people who came to play it, and the things that players recounted to me really shaped the way that I run my games to this day.

The first, and most pressing, constraint of the digital narrative experience is that it is nigh impossible to account for all the situational variables as your storyline becomes larger and more complex. Creating meaningful opportunities and implementing gamification are major components of this. Tabletop games tend to do a good job with game elements, but I see a lot of GM’s fail to give players good options in character progression.

When writing Orchestra, I found that writing game and narrative blended naturally into one combined process. There was a level of interesting interaction between game elements and narratives; players can work in their own explanation for how things happened and the only thing I had to do was create the basic impetus for a few events.

One of the things that IF does well when mixed with game elements is provide players with a sense of direction; the game elements fill in the gaps that otherwise would go unnoticed due to an inability on most writers’ behalf to actually write specific responses to every possible outcome. Players are able to visualize their avatar in such a way that they tell the story to themselves as it unfolds, and this is very similar to how characters in a tabletop game will build a story and persona around their players’ perceptions.

The obvious thing that this suggests is that these game elements can and should be used to encourage deeper character development.

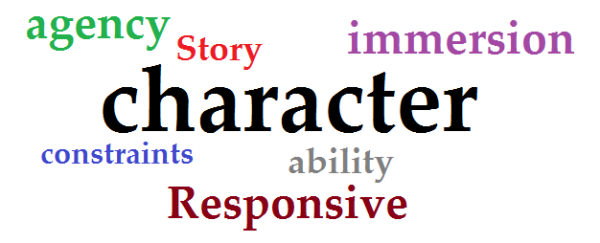

What does this mean? I’d say that it means that we have to be very careful when evaluating how we plan and run our games; it’s not just the act of writing a story, but encouraging players to use their characters as agents in the story. If we are to reach the largest possible audience, especially along the fringes of the people who currently play tabletop games, at the table it is critical to encourage the idea of the character as an agent in our players, stressing both the ability and constraints that a character has.

Likewise, I’ve found that my players’ favorite experiences come when the rules of the game don’t matter anymore, and they have become entirely immersed in the narrative; even when a character is killed or injured, the presence of a world with limits and opportunities is as important as the ability to execute a list of actions written on a character sheet. Unfortunately, this means that there’s a lot of potential work for a GM, and, as with any planning, stuff can go off the rails quickly, but a lot of this can be mitigated by considering what to plan and how to encourage players to follow paths that their character would take so that they can be satisfied without necessarily operating in a vacuum of direction that makes it difficult to respond to changing events.

The game should grant agency. I’ve always felt that the role of the GM is to work with players to build a story that’s interesting and fun for everyone, but I often see GM’s who just tell stories that the players want to tell or that they want to tell. Using plausible restrictions on players’ characters forces them to think inside the rule of the world, and it actually serves to humanize their characters. This makes it easier for players to connect with the non-player characters and events of the game, and gives them an idea that the universe that the events are taking place in exists as a coherent concept.

When we think of our favorite characters in fiction, almost all of them are constrained in a fairly major way by the world around them; their abilities are used in conjunction with the challenges they face to tell their journey, and as a GM it is possible to give players a memorable and satisfying experience in this way.

I think one of the things that stood out to me most when I applied things I learned writing IF to the tabletop was player perception. If I could align my users’ expectations with my work, or vice versa, they enjoyed the content more. If they expected to be a Bourne-esque supersoldier, I had to include things that allowed them to jump to that conclusion, but when I did they felt like my work was theirs in a vivid and experiential manner.

For comparison, one of the most frustrating experiences I ever had as a gamer was from EA’s reboot of Syndicate during the single player campaign. While the gameplay was actually far better than I expected, I was constantly frustrated by my lack of agency in the story. One of the deadly sins of storytelling is countermanding player expectations. While Kilo stood back and let events unfold, all I wanted to do was to get back into the action, and when major choices in the story came up he almost never wound up aligned with the people that I would have aligned with.

Giving players agency was as simple as learning what their expectations were; giving myself a little insight to the situation let me figure out what players want to do. When I run my games, I try to get an insight on what my players do. The paladin in shining armor will never strike a downed enemy, while the ruthless rogue will always throw in an extra stab for good measure. Because of this, I can plan narrative events that allow players’ characters to show their personality in an environment that responds to them—in the paladin and rogue example, adding a decision point involving incapacitated enemies gives players a chance to make a moral decision that would often be overlooked by staunch adherence to the combat rules of a system.