As I’ve gotten older, I’ve experienced significant shrinkage in my available time and effective attention span, so I’m unable to commit to a week-long/month-long/year-long campaign. For me, I’m all about convention games, 4-hour quick-sits at gaming stores, or “What are you doing this Saturday?” delves. Each of these has a definitive beginning and ending. Of course, the players are just getting to know their characters and each other when the game ends, but that’s a small price to pay for the mental mobility of a one-shot. Thus, here is my process:

Step 1: The Idea

Imagine bumping into a gaming superstar at a convention, and she says, “I’m interested in your 1 o’clock game. Tell me about it.” If your instinct is to say, “The year is 689 in the fog-shrouded time of the Ancient Dragons, and all the world stands silently as evil seeps from the lands below…”, you’ve just lost your superstar.

Imagine bumping into a gaming superstar at a convention, and she says, “I’m interested in your 1 o’clock game. Tell me about it.” If your instinct is to say, “The year is 689 in the fog-shrouded time of the Ancient Dragons, and all the world stands silently as evil seeps from the lands below…”, you’ve just lost your superstar.

Ideas are one sentence, the less thought given to them, the better. Don’t agonize over it, don’t examine every angle, don’t figure out the logic, the setting, or the plan. Come up with a single sentence that would make a player pause and say, “Really? Tell me more about that.” If you need to, drag out the dusty old Tome of Clichés: evil twins, betraying friend, early onset amnesia, the “more than he appears” character, working for the villain, and so on.

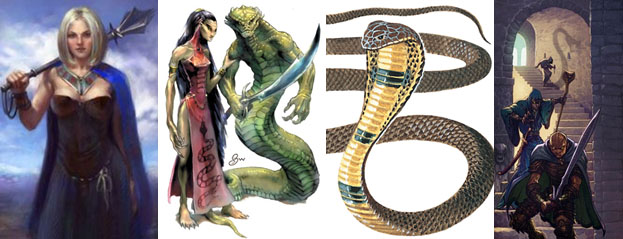

The party has to kill a lawful good high priestess and her snake servants.

Step 2: The Enemies

Using the excellent Monster Builder, make a list of the potential combat opponents, really uncorking your imagination and letting it spill all over the floor. Your goal is to have way more than you could ever use, varying the types of creature. Because the Monster Builder allows you to set the monster levels, don’t feel like you have to restrict yourself in your selection to just heroic, paragon, or epic monsters.

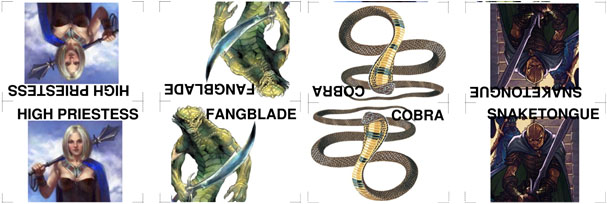

High Priestess, yuan-ti, giant snake, kobold, drake, kruthik, lizardfolk, snaketongue

Step 3: The Encounters

Decide on three set-piece encounters, using this pattern:

Encounter One

Use the KISYSDM method, or Keep It Simple, You Stupid Dungeon Master. You don’t know these players, they don’t know you, they don’t know their characters, and they don’t know each other. For these reasons, you should create a nice two-dimensional setting with few terrain challenges, and then insert brutes and minions. It’ll be easy on you and the players, and as a happy bonus, the players will figure out how to work together.

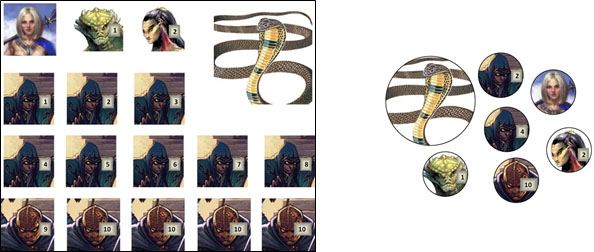

Use two (party level+1) brutes and 24 (party level) minions.

Note: According to Dave Noonan, minions should be worth 1/10 of a standard creature, and not the book-dictated 1/4.Trust me here, Dave’s right.

In a wide intersection, the party is attacked by two yuan-ti fangblades and their 20 snaketongue initiates.

Encounter Two

Break for roleplaying! Whether it’s a formal skill challenge or an informal wander-and-look, this offers a respite from the possibly hectic, probably grindy combat, giving the players a chance to interact with each other without the constant bleating from the DM.

The party investigates the snake-creatures and cultists that attacked them, researching the snake symbols worn and carried, talking to their back alley contacts, threatening the local priest who seems to be involved, and eventually tying the events to the high priestess, an upstanding cleric of Pelor who may be a servant of evil.

Encounter Three

As much fun as roleplaying is, many (most?) of the players may be getting antsy at this point, wanting to roll dice and hurt enemies. It’s time to give them that opportunity, in the form of an encounter that’s a good deal tougher than the first one.

Use one (party level+4) elite brute, one (party level+2) soldier or controller, two (party level) brutes, and 10 (party level) minions.

In the temple of Pelor, the party confronts the high priestess, discovering that she is, in fact, a victim, being controlled by a giant cobra who wants to RULE THE [whatever]. This battle will be against the giant cobra, the dominated high priestess, two yuan-ti abomination berserkers, and 10 spitting cobras.

Step 4: The Settings

By now, you should know the basic shape of the sites you’ll feature, so all you need to do is assemble your maps. Naturally, you can draw them yourself on Chessex Battlemats or Gaming Paper, or use the Wizards of the Coast Dungeon Tiles or Paizo Flip-Mats. Your artistic skill or your existing map items may influence the final settings, but if you approached your encounters in the broadest strokes, you can be flexible with the finished product.

For Encounter 1, I’d use my Paizo City Market Flip-Mat, and for Encounter 3, I’d use my Paizo Cathedral Flip-Mat. For Encounter 2, I’d keep it all firmly in the imagination, since the player characters should be wandering all over the city and interacting with lots of people.

Step 5: Getting Graphical

Using the jumbled expanse of the internet, locate good pictures for all the monsters and characters. This part of the process is both thrilling and infuriating, since I can often find a few great examples and several terrible ones. Make use of the Wizards of the Coast Image Archive, and, of course, the Google images site is always a fun ride, especially if you don’t mind the occasional totally naked non sequitur.

Step 6: Monster Markers

During game play, I always prefer markers over miniatures, and here’s why:

- Multiple miniatures can clutter and confuse the board, and sure, that may seem like so much “fog of war,” but in practice, it’s just distracting.

- Typically, DMs will have ALMOST enough miniatures for a given encounter, resulting in, “this ogre is actually an ice demon,” or, “this horse is actually a spider,” or, “this halfling is actually a dragon.”

- If the player characters are the only three dimensional creatures on the battle map, it correctly elevates them as the most important beings present. This story is about them, not the opponents.

In a Microsoft Word document, lay out the monster images, cropped to the faces (small and medium creatures to 1.25″ x 1.25″, large creatures to 2.25″ x 2.25″, and so on) and numbered sequentially, and then print these pages onto white full-sheet shipping labels.

After sticking the pictures onto shoebox cardboard (good weight, and available for free at your local shoe store), cut the markers using the greatest thing to ever come out of craft stores, the sized circle punch. I use the 1″ nesting punch and the 2″ squeeze punch.

Step 7: Initiative Cards

In a Microsoft Word document, lay out the character and monster images on labeled folded cards, which will sit like tents in front of the DM, tracking initiative order and also displaying images of the monsters. I’d recommend printing on cardstock, white for the monsters and bright yellow or pink for the characters, for easy identification.

Step 8: Final Touches

At this point, the one-shot is finished and ready to run, so you should take a step back, maybe see a few other adventures to cleanse your palate, and come back with a fresh perspective. You want to reread this one-shot from the point of view of the players who will be experiencing it, asking the following questions:

- Is there a clear through line? Does the progression through the encounters make sense, or does it feel disjointed and chaotic?

- Will the puzzles or riddles or mysteries be painfully obvious to even the stupidest players? Remember that this will be the very first time these players will see these elements, and they don’t actually know the answers.

- Are there parts of the adventure that will spotlight specific player characters? Will the thief be able to pick a lock? Will the bard be able to sing a song? Will the fighter be able to crack some skulls?

- Are there any parts of the adventure—the monsters, their powers, the settings—that can be exploited by the players? Is this really a bad thing?

Note: If you find any parts that can be exploited, do NOT change them. Just come to terms with them. Allow it to happen. Become a leaf on the wind.

- Through Line. The adventure story is quite simple, starting with an attack, moving to an investigation, and concluding with the big snake battle. The party halts the growing darkness, saves the high priestess (hopefully), and lives to fight another day (again, hopefully).

- Puzzles/Riddles. The investigation is freeform, merely requiring the player characters to poke around and ask questions. They’re looking for the WHYS (why were we attacked?), and then moving onto the WHAT NOWS.

- Spotlight. If you’re providing pregenerated characters to the game, it becomes much easier to develop spotlights, since you’ll know exactly what the characters are capable of. Even so, you can assume the party will include strikers and probably a defender or two, which explains the high-damage, low-defense brutes, and it might include a controller, so there are piles of minions. If I knew an undead-bashing cleric was coming, I might want to toss in some zombies too.

- Exploits. The party might decide to take prisoners in that first encounter, which could screw up my investigation during the second encounter. They could also turn the second encounter into their Traveling Torture Tour of this nameless city, “Tell me what you know or I’ll cut off another finger!” Finally, and most troubling, they might elect not to look into the attack, deciding, “We were attacked by snake-men and cultists. Weird. Let’s go to the inn and drink.”

What About Dungeons?

Maybe you read this and thought, “That’s all well and good, but I want to create a dungeon one-shot. Dungeons don’t work as encounters, but as a player-selected series of rooms. I can’t control which one they’d go to first, then second, then third.”

Except, of course, you can. You just don’t have to tell the players you’re doing it. Your first encounter might be the ORC LAIR, which covers five interconnected rooms and contains a total of 30 orcs, which lay into the characters in waves. This would still look like a dungeon but play like a one-shot.

Conclusion

Believe it or not, I’m not suggesting that every one-shot has to adhere to this structure—easy battle, non-combat, tough battle—but I’ve found it to be a reliable template for my own quick delves or convention games. In the snake example I gave, it would still work even if I shuffled the encounters a bit:

- Encounter 1: Church representatives ask the party to investigate their high priestess who’s been acting strangely, which means we lead off the adventure with non-combat.

- Encounter 2: During the investigation, snake men attack the party, and flee once they realize how tough and scary the party is.

- Encounter 3: The party pursues the snake-men to the cobra lair, and fight the snake cult.

For any of these, the biggest challenge for the DM would be believably connecting the encounters, and that’s where I can load the party up onto a story-train, and click-clack, click-clack, click-clack, we’re onto the next encounter through a cut-scene. In a time-sensitive game, like at a convention, this approach always works, and the players tend to be more forgiving.

So, do you want to see how I wrote up this example adventure? I didn’t go into a whole lot of detail, but then, I rarely do.

Download Adventure-FaithLikeVenom, which sounds like a combination George Michael and Madonna song. Man, I’m old.

Great article! This is a great format and sometimes, that’s what us DMs need- not just a formula for an encounter, but a formula for a string of encounters. If we could slap together a handful of templates like these, no DM would ever have an issue making an adventure again. I’ll definitely be using this in the future.

Well done! This is a great outline of how to throw something together for an awesome evening of gaming. I can completely agree with Dave Noonan’s assesment of minions. I tend to throw them at my group in massive hordes like that. Plus it really gives the wizard a chance to show off.

A very nice guide. Excellent advice on focusing on what is important for a one-shot.

@Quirky DM: Wonderful! If you do put together an adventure or two, I’d love to see them. Maybe you can post them on your site and give a shout-out.

@Thorynn: I’ve never found a player who’s said, “Man, I hate minions.” They serve exactly the purpose they were created for, making the PCs feel completely amazing, and I report this from both sides of the screen. More minions, more minions, more minions!

@BrianLiberge: Thanks! I realize this wouldn’t translate to a campaign style game, but it really has worked for me for conventions and delves.

Monster Markers are nothing new, but I have now been finally convinced to try them out. Thanks!

Faith Like Venom: Sounds like a great name for a band, not just a song!

@ Tourq: Agreed. Thanks Dixon for the great tip on homemade markers!

@Chris Stevens: I would never claim that I invented monster markers (or initiative cards or the lightbulb), but I do feel like I can make an excellent argument that I have perfected them beyond mortal comprehension.

@John Lewis: In full disclosure, it is my hair metal cover band. We sing a lot of Poison and White Snake.

@Colin Dowling: You’re very welcome. Perhaps the biggest challenge continues to be finding good fantasy pics.

@Dixon – is the band composed exclusively of Big Hair Halflings?