The Next Epic, part two

The evolution of D&D with regards to mandated end-points of character progression – and ways to bypass those end-points – was not a precise one. While OD&D had largely been silent on the matter, and BD&D had gradually pulled back the curtain on higher and higher levels (save for demihumans, who were capped at comparatively low levels) all the way to playing as a deity (and subsequently evolving beyond even that), the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game would not present quite as coherent a picture.

Advanced D&D First Edition

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons is presumably “Advanced” in relation to the Basic edition of the game. The truth of that idea, however, is somewhat murky. AD&D officially debuted in 1977, with the release of the Monster Manual. It wouldn’t be until 1978 that the Player’s Handbook was released, followed by the Dungeon Master’s Guide in 1979.

By contrast, the very first “basic” set (by Dr. J. Eric Holmes, as mentioned in the previous article) was itself only released in 1977, the same year as the Monster Manual – by contrast, the subsequent iteration of the Basic rules (which would be the first half of B/X), wouldn’t appear until 1981, by which point AD&D was well-established whereas Basic wouldn’t achieve its “final form” until the Mentzer boxed sets, which began in 1983.

This is all worth mentioning because it reminds us that AD&D wasn’t originally meant to be the next logical step up from “Basic” D&D (though it would eventually be branded that way), so much as it was taking the same basic ideas from their shared predecessor (OD&D) and running in a different direction with them. The foundation is the same, but the implementation is where things differed.

This “similar, but different” approach can be seen in the AD&D game’s approach towards upper levels and divine ascension. Whereas BD&D’s allowed only humans to pick their class, with demihumans having their class define their race (e.g. you could start the game as a 1st-level human cleric, whereas if you wanted to play an elf then you were a 1st-level member of the elf “class”), AD&D allowed for race/class combinations for all characters.

These combinations, however, were highly limited. Even leaving aside that races and classes had minimum (and maximum, for races) ability score requirements, AD&D implemented the idea of humanocentricism by including hard limits on how many levels demihumans could attain in various classes… presuming that they could take those classes at all, since each type of demihuman could only take certain classes to begin with. Humans, by contrast, could take levels in any class they wished, with no upper maximum.

Of course, even these hard-and-fast rules had their exceptions. Each demihuman race in the Player’s Handbook had one class in which they could advance without limit, just like humans (this was the thief class for all demihumans save half-orcs; for them, unlimited potential was found in the assassin class… which was rather ironic, as the next sentence will show). Likewise, no race, not even humans, could advance endlessly in classes for which only a finite number of levels existed, such as with druids or assassins – once you hit the maximum level in either of those classes, there was no further advancement to be had (unless you were already multiclassing if demihuman, or could dual-class if human).

This was the first time that the D&D game, in any incarnation, featured level advancement that was potentially unlimited. Strictly speaking, if you were of the right race/class combination, the sky was the limit for how high you could climb. Surprisingly, however, that degree of advancement made very little difference in a character’s overall power.

The reason for this is that, at a certain point, gaining new levels offered virtually nothing. Every class stopped gaining new Hit Dice around 10th level or so, after which point you gained only a small, set number of hit points, usually ranging from 1 to 3 (to which you didn’t get to add your Constitution bonus). Likewise, your saving throws and to-hit bonus tended to top out at around level 20.

In other words, your character didn’t gain very much at all by leveling past 20th level or so. You got a new hit point or three, but that was about it. So your 75th-level fighter and your 20th-level fighter weren’t going to be that much different, save that the 75th-level fighter was a better meat-shield (one notable exception to this, however, was that spells with effects based on caster level had no cap – that meant that your 75th-level wizard could unleash 38 magical blasts with a single casting of magic missile!).

Now, your character might have gained a supreme amount of magical items by that point, and possibly political powers as well if they’d chosen to dabble in rulership (the game tended to suggest that around “name level,” which was usually around 9th, that your character would begin to have a political impact on the world around them), but this wasn’t mandated by their level, being the result of the character’s in-game exploits.

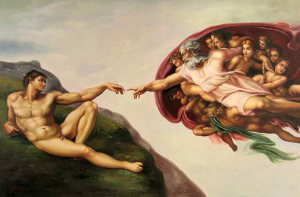

One alternative goal, for those who wanted to try for it, was divine ascension. Introduced with the Deities & Demigods book in 1980 (and easily predating BD&D’s Immortals boxed set, which didn’t debut until 1986), divine ascension was highly different from how AD&D’s Basic counterpart would define it. True, both included a set of difficult conditions that had to be fulfilled before your character would be accepted into the ranks of a pantheon, but the similarities ended there.

For one thing, AD&D divine ascension was not a natural end-point for character progression. Indeed, an AD&D character that didn’t run aground of racial or class-based level limits could theoretically level-up forever (presuming that they found some way of dealing with problems of age), all the while remaining mortal.

A much more stark change between the two games was that, for AD&D characters that became gods, their apotheosis marked the end of their participation in the game, at least insofar as being a player-character went. Deities & Demigods explicitly stated that the newly-ascended deity was given non-player-character status, making them under the control of the DM.

Further, there was no option for their “removal” from the game world. Whereas BD&D’s Immortals could, through great difficulty, ascend beyond the game world and its rules, AD&D’s gods had no such lofty goal to shoot for. Once you were a god, you were pretty much an established god of the game world from that point on (unless the whims of the DM had some cosmic fate befall your divine NPC).

This formula, where your class and race combination determined if you would have unlimited potential or hit a hard cap, with divine ascendancy as an orthogonal option for character retirement, would be comparatively unchanged in AD&D Second Edition… but what changes it did have would be notable indeed.

Advanced D&D Second Edition

The Second Edition of AD&D introduced several twists on many of the ideas regarding upper-level limits for characters that its predecessor had introduced. For example, while demihuman level limits remained in the game, new rules about allowing demihumans to exceed these limits appeared (though these exceptions were dependent on having exceptional ability scores, and only allowed those limits to be pushed by a few levels). More notably was the fact that no class allowed for unlimited demihuman advancement; that was now a privilege reserved for humans alone.

Of course, that privilege was to be taken in light of a far more dramatic change: all classes were now twenty levels long. While not presented as a hard cap (the Second Edition DMG even said that advancing beyond 20th level was “theoretically possible”), it was fairly well understood to be just that; the lack of information about how many experience points were needed, and how many hit points were gained, meant that adventurers were effectively capped at 20th level.

Interestingly, this cap was first extended not by a generic rulebook, but by the Dragon Kings supplement for the Dark Sun setting. Dark Sun had, from the first, been presented as a very tough campaign world (PCs were told to make their starting characters level 3, rather than level 1), and this book was the natural conclusion to that. It showed how all types of classes (albeit with racial limitations, though ones tailored for that campaign world) extended to a new limit: 30th level.

Despite the fact that this was a campaign-specific supplement (and as such had campaign-specific aspects to these higher levels), it had impact for all Second Edition D&D characters; indeed, since the campaign settings of Second Edition AD&D were all set in the same multiverse, there was ample understanding that these rules could be used for all 21+ level characters.

This approach was eventually formalized in the generic supplement Dungeon Master Option: High-Level Campaigns. Here the 21st-through-30th-level rules were given in a generic presentation (differing from those presented in Dragon Kings), allowing them to be easily used for characters in all types of campaigns. It was also here that the hard cap on gaining levels was formalized, as the book out-and-out stated that no character could ascend beyond 30th level.

Of course, divine ascension was still possible. Indeed, divine ascension rules were presented fairly early on in Second Edition’s (in the Legends & Lore supplement, which debuted roughly a year into Second Edition), and were reiterated again in the High-Level Campaigns supplement as well. There is little to merit special attention here, however, as Second Edition’s divine ascension rules were near-totally the same as their First Edition counterpart, differing only in minor details of how to perform the act of apotheosis itself.

Indeed, the most noteworthy aspect of Second Edition’s divine ascension rules is in how they’re perceived compared to previous editions of the game. Like Basic, ascending to become a god was something that naturally seemed to follow once you ran out of available levels to gain – when there was no further advancement to be had, godhood is the only way left to go. Unlike Basic, but in the vein of First Edition, however, this is a closing chapter to a character’s career; something done as a grand send-off for your character, rather than entering a new phase of play. In this regard, Second Edition can be said to have split the difference between its predecessors.

Next time, we’ll look at how Third and Fourth Edition handled the questions of epic levels and divinity.